Quiulacocha

I first visited Cerro de Pasco, the oldest mining settlement in Peru, two decades ago. I have returned more than a dozen times. The city was built amid mountains laden with silver, copper and zinc in a frigid corner of the central Andes, at a dizzying elevation of 4,300 meters. For most of its history, Cerro de Pasco was the crown jewel in Peru’s voracious mining industry, a place where Spanish conquistadors and American magnates made fortunes that trickled down to the city’s wealthy enclaves.

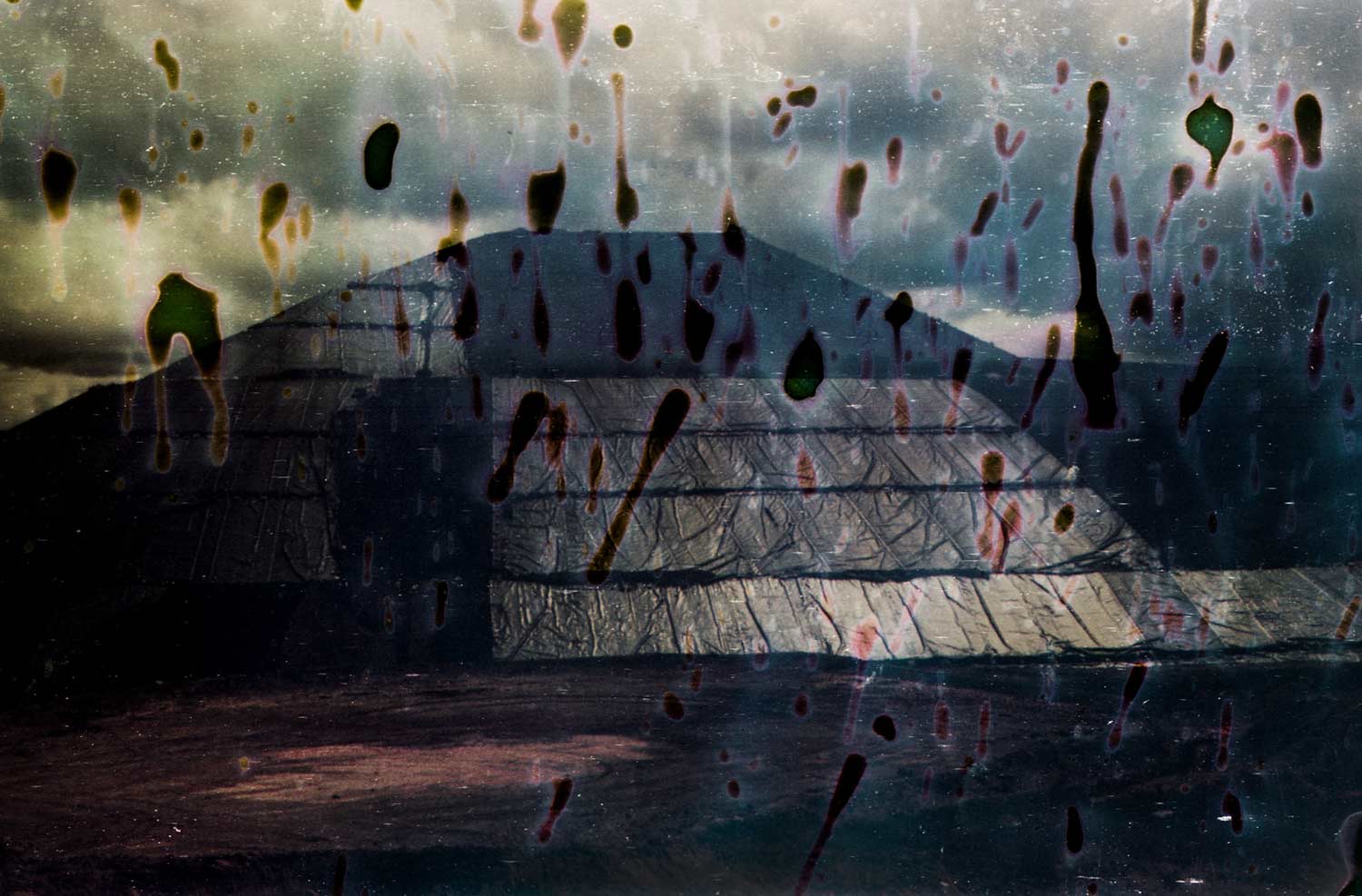

By the time I arrived, on assignment as a photojournalist for a newspaper in the capital Lima, the city had been in decline for decades. The blighted landscape resembled a battlefield. A massive open mining pit spiraled endlessly into the earth, evoking the concentric circles of Dante’s inferno. Along its edge, houses crumbled in abandoned neighborhoods. In others, life went on amid heaps of toxic waste, offering a dystopian glimpse of a future of environmental ruin.

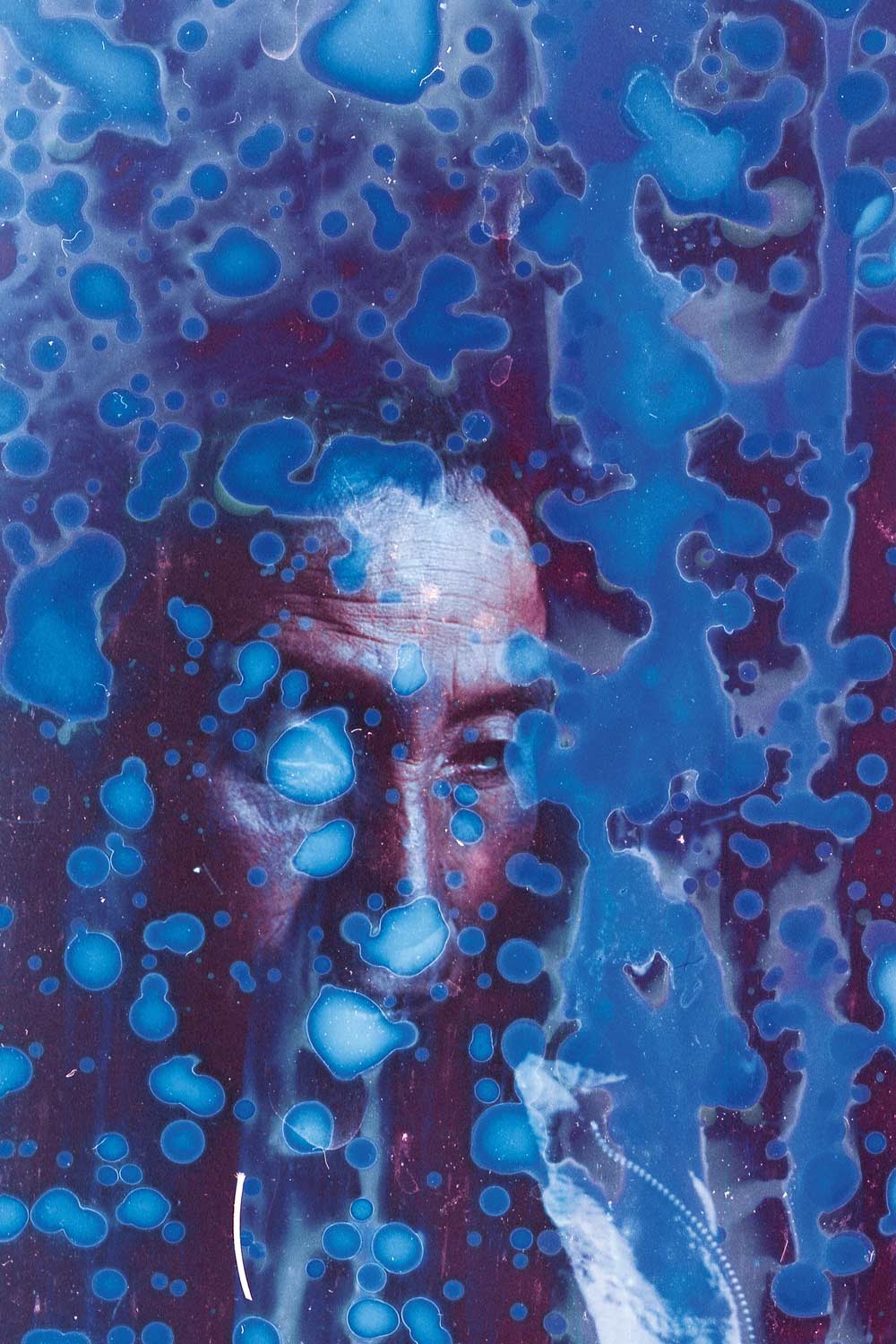

I soon learned the city was home to clusters of sick children. They suffered from stunted growth, leukemia, debilitating learning disabilities and daily nose bleeds. Parents said the mine was polluting their blood. Eventually. Health authorities found hundreds of children had unsafe levels of lead, arsenic and mercury running through their veins. But that did little to change their situation. Families have had to fight for access to even basic health care for their children. Doctors ask them to move away to avoid the source of pollution, but few can afford to leave the city for good.

Cerro de Pasco embodies a paradox at the heart of mining in Peru. Mining powers the national economy, but it also devastates life in places where it takes place. Centuries of mining have turned much of Cerro de Pasco into a toxic waste site. The ongoing search for metals in dwindling deposits keeps the city alive, even as it locks in more pollution for the future. Each time I visited Cerro de Pasco, the gaping pit in the middle of it grew a little bigger and the list of sick children a little longer. And yet, most Peruvians were unaware of their cases.

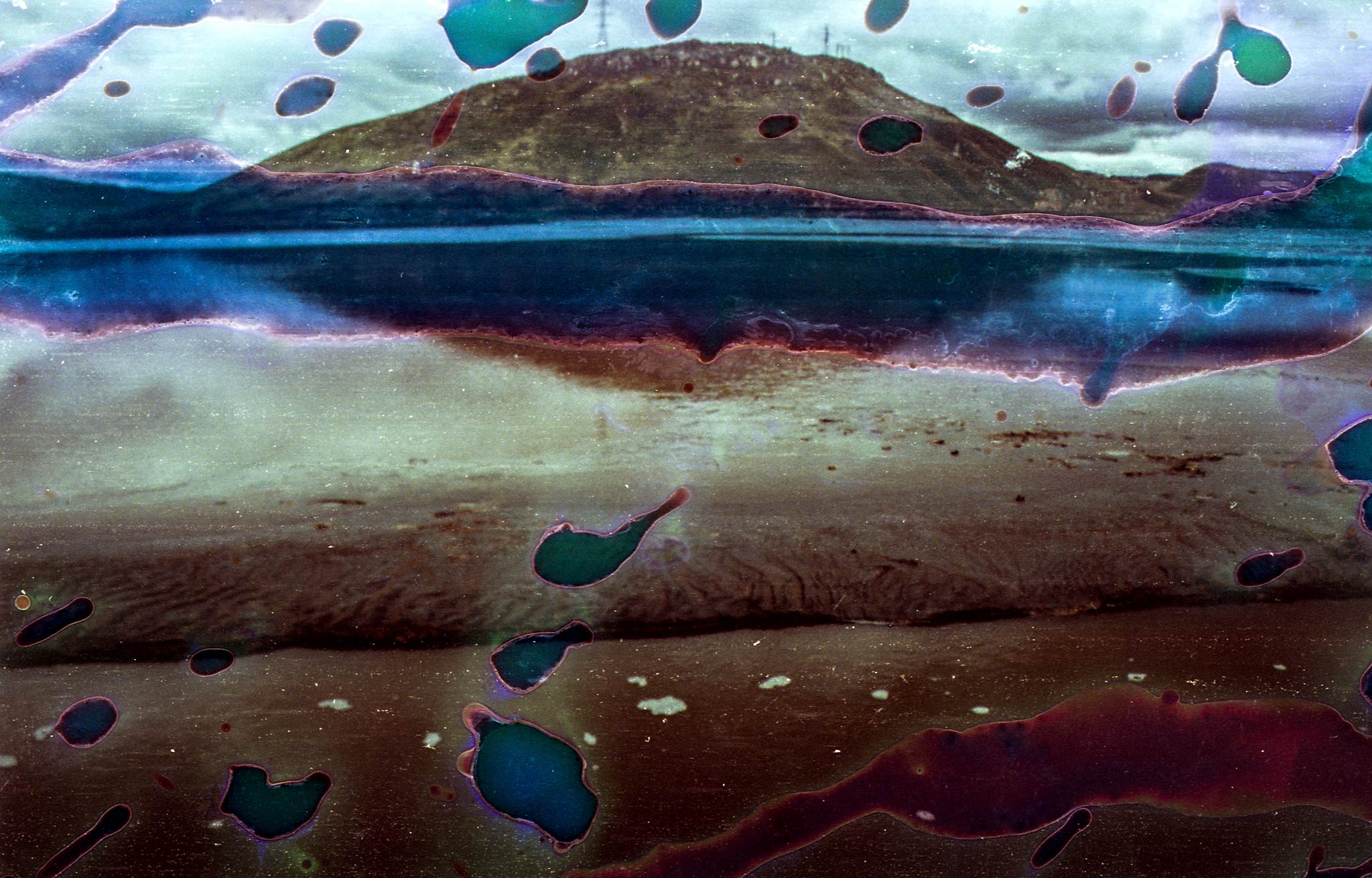

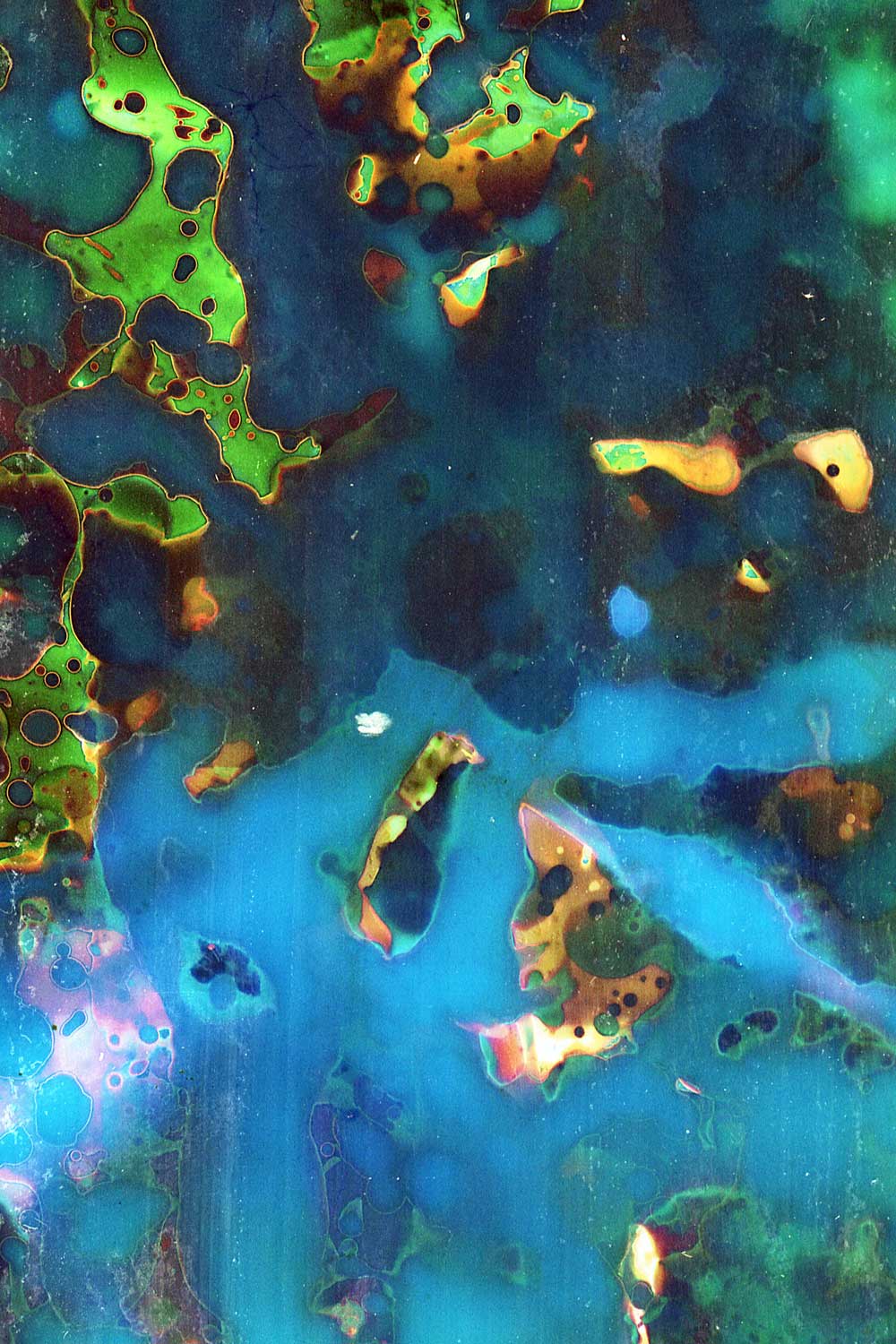

I got the idea for this project at Lake Quiulacocha in Cerro de Pasco. Named in Quechua for the Andean gulls that once flocked to its shores from the Pacific coast, no sign of life survives in it today. Instead, puffs of foam crown orange waters that soak more than 600,000 cubic meters of mining waste left behind by the mine’s operators, including the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Copper Corporation and the state-owned Centromin Perú S.A. The heavy metals that seep into the watershed at the unlined bottom of the lake read like a list of toxic substances: lead, mercury, cadmium, arsenic, aluminum, boron, copper, cobalt, iron, manganese, selenium.

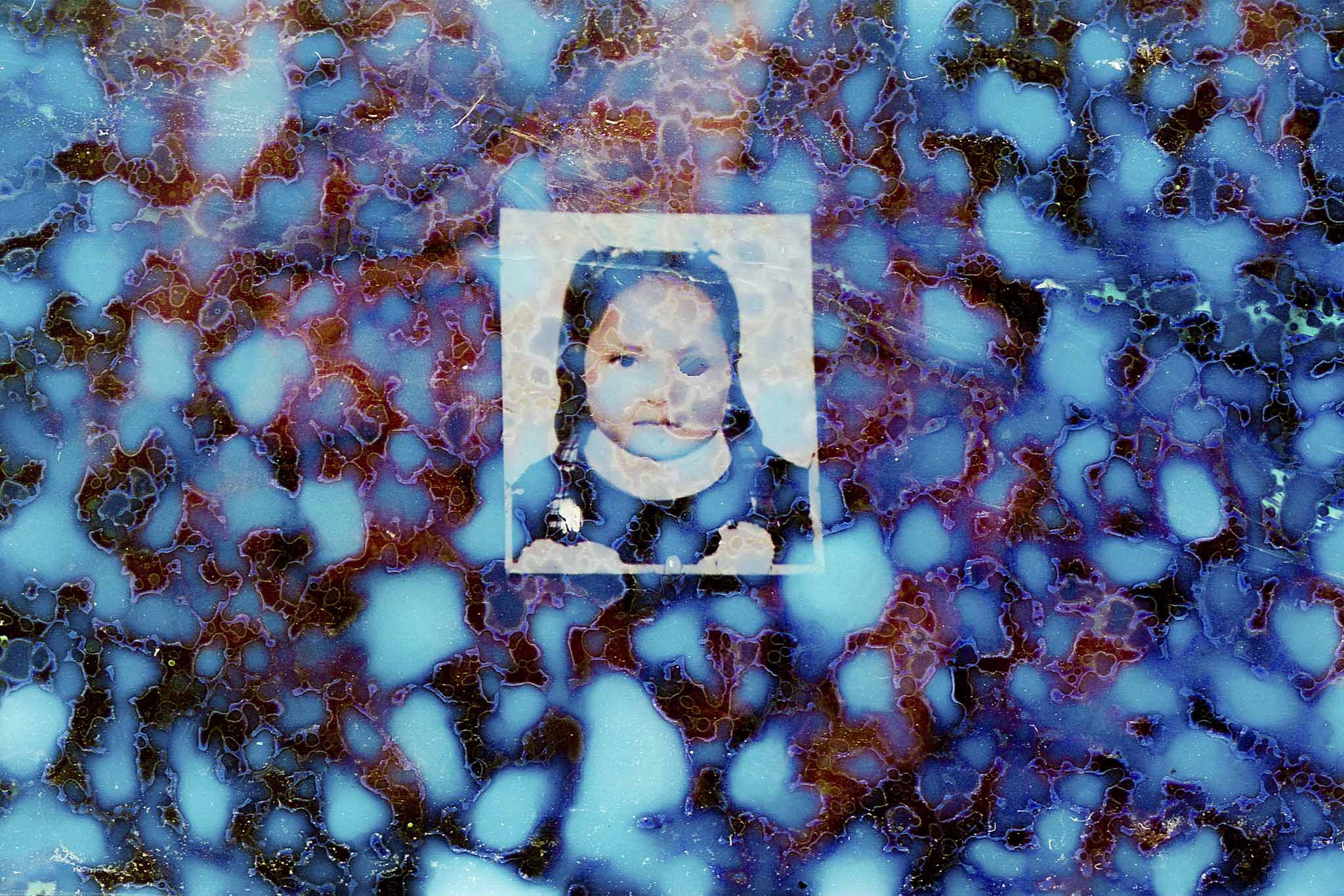

Three years ago, I started collecting samples of water from Lake Quiulacocha to use in developing photographs I take in Cerro de Pasco. The acidic liquid produces stains and hues that manifest unpredictably across faces and landscapes, mimicking the indelible imprint of pollution on life. It was—and is—an attempt to expose the corrosive impacts of mining on people and the environment that aren’t always evident—to make visible what society prefers remain invisible.

Mining pollution is such a widespread problem in Peru that it is rarely covered in local media. Thousands of contaminated sites are on a waiting list for clean-up. Health impacts can take years to manifest, and often go unnoticed. Even today, despite growing awareness of the problem, authorities have done little to support the sick children of Cerro de Pasco. I still wonder if it is possible to truly transmit their plight in a visceral way through photography.

I’ve taken thousands of pictures in Cerro de Pasco, which still proudly calls itself “the capital of mining in Peru.” Some neighborhoods I once walked through are now rubble. Some of the children I profiled are now young adults who still struggle with chronic and incurable illnesses. One has died. This is a sample of what I have witnessed. An attempt, perhaps insufficient, to reflect the true cost of mining.